Few threats to global financial integrity are as brazen as Hezbollah’s exploitation of vehicle theft and resale networks. From luxury SUVs stolen in Canadian suburbs to second-hand cars shipped out of American ports, the group has perfected the art of transforming ordinary commodities into lifelines for terrorism financing. Canada’s most recent national assessment underscores how organized criminal groups, terrorist operatives, and financial enablers are intertwined in these schemes, with Hezbollah positioned at the center of one of the most complex illicit networks in the world.

Table of Contents

Vehicle Theft Laundering And Terrorist Financing

The mechanics are deceptively simple. A vehicle is stolen or fraudulently obtained, often through leasing scams or fake identities. That vehicle is then placed in a shipping container and sent across the ocean, frequently routed through hubs such as the Port of Montreal. By the time the car reaches a destination market in West Africa or the Middle East, it is sold for cash in largely informal economies. The cash proceeds, once pooled, become part of Hezbollah’s shadow treasury. Couriers, hawala operators, and currency brokers then channel funds directly into Lebanon, ensuring that the group retains its military capacity and political influence despite international sanctions.

This form of laundering is not limited to vehicles. It merges with narcotics trafficking, fraudulent trade invoices, and even the abuse of charitable institutions. Yet automobiles remain one of the most consistent revenue streams because they are high-value, easy to move, and simple to disguise as legitimate exports.

Hezbollah’s History With Car-Based Money Laundering

The roots of Hezbollah’s involvement in the automobile trade stretch back decades. Long before regulators began paying close attention to trade-based money laundering, the group was leveraging the used-car sector as a financial artery. Investigations in the early 2000s revealed that Lebanese financial institutions wired hundreds of millions of dollars to American car dealerships, many located in states such as Michigan and Maryland. Cars purchased through these channels were shipped en masse to West Africa, a region with large Lebanese diaspora communities deeply linked to Hezbollah’s networks.

Once cars were sold in African markets, proceeds mixed with narcotics revenues and other criminal funds. The money was then moved into Lebanon through a sophisticated system of cash smugglers and couriers. Beirut’s Rafic Hariri International Airport became a notorious hub, where Hezbollah-controlled security allowed large volumes of currency to pass unchallenged. These funds were ultimately absorbed into the group’s wider financing system, supporting both social programs and military operations.

The scale of this trade was staggering. Estimates suggested that at its peak, the laundering machine generated hundreds of millions of dollars monthly. For Hezbollah, the car trade became not only a source of profit but also a cover for integrating illicit proceeds into the global financial system. Unlike narcotics or weapons shipments, cars raised fewer suspicions, especially when accompanied by seemingly legitimate paperwork and financial transfers.

Canada As A Strategic Hub For Hezbollah

Canada has long been a favored base of operations for Hezbollah. By the early 1990s, operatives with ties to the organization had established themselves in major Canadian cities, embedding within immigrant communities and exploiting the country’s robust financial system. Intelligence reports from the period indicated that Hezbollah agents used Canada to raise funds, purchase equipment, and launder money for the group’s international operations. Some networks even received direct “shopping lists” from Lebanon, which included military supplies and other items to be shipped back via courier packages.

Canadian banks were unwitting participants in this cycle. Accounts at leading institutions were used to move hundreds of thousands of dollars, while life insurance policies were taken out on Hezbollah operatives who would later be killed in conflict with Israel. Hezbollah also engaged in large-scale fraud and extortion, targeting Lebanese expatriates in Canada and pressuring them into purchasing vehicles or making financial contributions.

The government officially banned Hezbollah in 2002, listing the organization as a terrorist entity in its entirety. However, proscription did not eliminate its presence. The Port of Montreal in particular became a focal point for smuggling, with reports of cars being stolen in Ontario or Quebec, funneled into containers, and shipped overseas. By the 2010s, extortion and racketeering cases further highlighted how Hezbollah-linked operatives continued to exploit Canada as both a source of revenue and a logistics base.

The Financial Crisis Driving Renewed Activity

Hezbollah’s reliance on illicit funding streams has intensified in recent years. The group faces unprecedented financial strain. Prolonged conflict with Israel destroyed large segments of its arsenal and infrastructure, while Lebanon’s own economic collapse limited the group’s ability to draw on domestic resources. Although Iran remains its primary sponsor, Tehran itself suffers under heavy sanctions and financial constraints. Moreover, geopolitical shifts, such as the downfall of allied regimes and intensified Israeli operations, have squeezed traditional supply routes.

The financial shortfall is immense. Reconstruction needs in Lebanon following recent conflicts are measured in the billions, yet foreign donors have withheld aid absent meaningful reforms that would curtail Hezbollah’s influence. Iran’s initial injections of cash are insufficient to cover the gap, leaving Hezbollah in a desperate search for alternative funding streams. Against this backdrop, the group has doubled down on its criminal enterprises, including vehicle theft and smuggling, as essential stopgaps to sustain its operations.

Even fractional gains from car theft networks become critical. A single shipment of luxury vehicles can yield millions in cash. While Hezbollah may only take a portion of the total proceeds—sharing revenue with local gangs, brokers, and transporters—these portions accumulate quickly. For a group under financial siege, every dollar extends its capacity to resist political or military pressure.

Current Dynamics Of Hezbollah’s Vehicle Laundering

The resurgence of large-scale car theft in Canada provides fertile ground for Hezbollah’s financing. Auto thefts have soared in provinces such as Ontario and Quebec, with insurers and law enforcement agencies describing the situation as a national crisis. Thousands of vehicles disappear annually, and while some are resold domestically or dismantled for parts, a significant share is funneled into international smuggling pipelines.

At the Port of Montreal, authorities have intercepted shipments containing hundreds of high-value SUVs, pickup trucks, and luxury sedans. Operations like these highlight only the fraction of smuggling attempts that are detected. Once loaded into containers, vehicles are difficult to trace, and customs authorities face overwhelming volumes of legitimate cargo that obscure illicit consignments. The destination markets frequently include West Africa and the Middle East, regions where Hezbollah maintains strong networks.

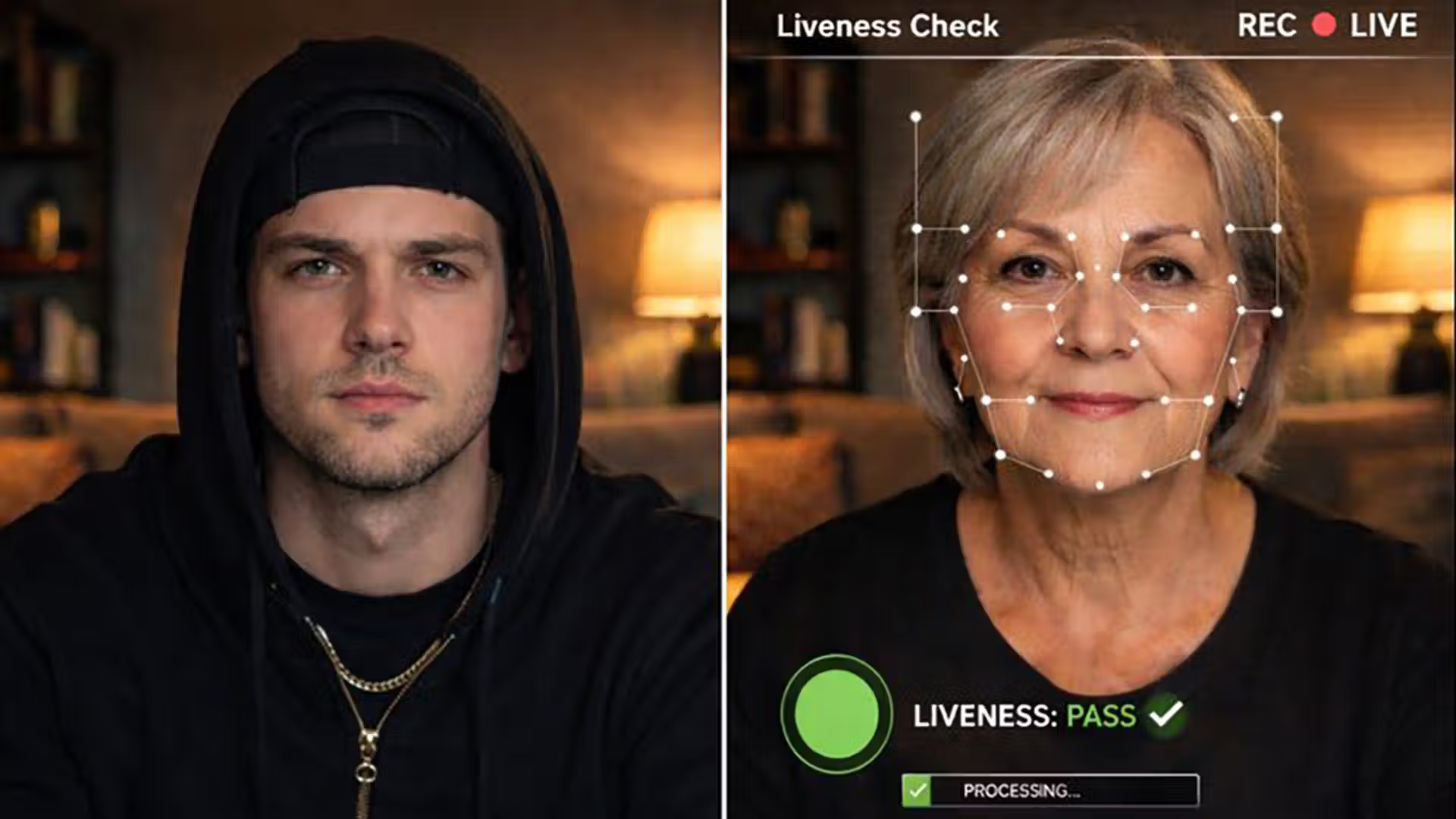

Hezbollah’s involvement is rarely direct. Instead, the group leverages layers of intermediaries—organized crime groups, diaspora facilitators, and corrupt brokers. This approach allows Hezbollah to distance itself from overt criminal activity while still profiting from the proceeds. Stolen cars are sold for cash, funds move through hawalas and couriers, and eventually the money resurfaces in Lebanon. The model is resilient precisely because it does not rely on any single actor or country, making enforcement a daunting challenge.

Final Reflections On Terrorism Financing And Illicit Trade

Hezbollah’s car laundering schemes illustrate the convergence of terrorism financing and organized crime. They show how ordinary commodities, stripped of context, can become tools of war and political influence. Vehicles stolen from Canadian driveways or American dealerships ultimately help finance weapons, salaries, and propaganda thousands of miles away. The international community has attempted to restrict Hezbollah’s funding through sanctions and proscription, but the adaptability of these networks demonstrates the limits of conventional tools.

Disrupting such schemes requires more than reactive seizures. It demands a fusion of financial intelligence, trade monitoring, and cross-border law enforcement cooperation. It requires closing gaps in customs processes, tightening oversight of shipping containers, and dismantling informal value transfer systems that move cash outside regulated channels. Perhaps most importantly, it calls for understanding that terrorist financing does not always look like weapons or drugs—it can be embedded in the movement of cars, the issuance of insurance policies, or the daily transactions of seemingly ordinary businesses.

As Hezbollah navigates financial crisis, its reliance on crime-based financing will only deepen. Unless systemic weaknesses are addressed, the group will continue to exploit the global car trade as a lifeline. And every shipment that escapes detection is not just a stolen vehicle—it is another step in financing violence, prolonging instability, and undermining the fight against international terrorism.

Related Links

- Proceeds of Crime Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Act

- FINTRAC Official Website

- Canadian National Risk Assessment on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

- Public Safety Canada National Strategy on Countering Crime

- UN Security Council Resolutions on Counter Terrorist Financing

Other FinCrime Central Articles About Hezbollah’s Financing Networks

- OFAC Hits Hezbollah with Fresh Sanctions Shaking Lebanon’s Banking Sector

- Hezbollah Financier Sentenced for Role in La Shish Conspiracy

- Massive $1.8Bn Terrorism Financing Network Linked to Hezbollah Uncovered

Source: Long War Journal, by David Daoud

Some of FinCrime Central’s articles may have been enriched or edited with the help of AI tools. It may contain unintentional errors.

Want to promote your brand, or need some help selecting the right solution or the right advisory firm? Email us at info@fincrimecentral.com; we probably have the right contact for you.